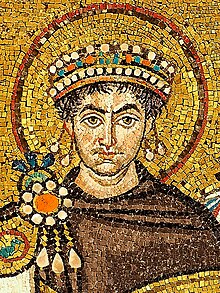

Mosaic of Justinian. Basilica San Vitale (Ravenna)

On 541 AD a plague broke out in the Byzantine empire.

According to the Byzantine historian Procopius, the best primary source of the period, the epidemic appears to have begun around the port of Pelusion, near Suez in Egypt. ”Then it divided and moved in one direction towards Alexandria and the rest of Egypt, and in the other direction it came to Palestine on the borders of Egypt; and from there it spread over the whole world, always moving forward and travelling at times favorable to it.” (Procopius, The Plague, 542) The plague reached Constantinople in the spring of the 3rd year of the Irano- Byzantine war (542 AD), and lasted four months with the period of greatest virulence lasting about three months. It killed nearly half the Byzantine capital’s population. The means of transmission of the plague was the black rat (Rattus rattus), which lived in the grain-storage warehouses in Egypt, the breadbasket of the Mediterranean world, and traveled on the grain ships ferrying grain from Alexandria to Constantinople. Fleas born on the backs of the rats infected humans with the bubonic and septicemic forms of the plague (Procopius, The Plague, 542). Not even the emperor Justinian escaped the epidemic, which named after him.

From Constantinople, the plague spread east into Asia Minor, west to Greece, Italy, France and Spain, and north to the British Isles, becoming the most lethal pandemic until c. 750 AD when it finally vanished. The plague of Justinian is considered the worst phase of the epidemic, even though it lasted only 4 months because the rat and human populations died before perpetuating the disease (North J.).

Five years before the appearance of the plague in Byzantium, Procopius wrote about the catastrophic climate change that took place in Constantinople : “during this year (536) a most dread portent took place. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness … and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear.” (Procopius )

A similar description comes from Italy. Cassiodorus, historian and praetorian prefect of king Athalaric, wrote to a subordinate: “The sun … seems to have lost its wonted light, and appears of a bluish color. We marvel to see no shadows of our bodies at noon, to feel the mighty vigor of the sun’s heat wasted into feebleness, and the phenomena which accompany an eclipse prolonged through almost a whole year. We have had … a summer without heat … the crops have been chilled by north winds … the rain is denied (Linden 2006, p. 57)

The decrease of temperature during that period, accompanied by social disruptions and war, led to catastrophic harvest failures and food scarcity that induced migration from rural regions toward cities. Accompanying the hungry migrants was an increased rat population carrying a highly infectious disease. They had found shelter in carts of supplies or were brought by grain ships to the city-ports.

Agricultural work stopped as a result of deaths and of flight. According to John of Ephesus, abandoned cattle, sheep, goats and pigs scattered over the mountains; fruits ripened with no one to harvest them; the fields of grain remained unharvested and the grapes uncollected. On the other hand, farmers living in Lycia decided that they would avoid plague staying away from the city, so there was a shortage of grains, wine and wood.(Atkinson, J.,p.15) Famine occurred in the Byzantine empire in 542 and again in 545 and 546 AD. In Constantinople there was a shortage of wheat and wine while goods, commodities and services became very expensive because of the shortage of human resources.

The plague had tremendous economic consequences in the empire. Its economy was depended on agriculture thus the drastic decrease of population and the loss of farmers was followed by food shortage and a severe shortfall in state income. The epidemic also contributed to the shrinkage of the military force. You can read here about the economic consequences of the plague and its cultural and religious effects.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Atkinson J. The plague of 542: Not the birth of the clinic

Bilich R. Cr., Climate Change and the Great Plague Pandemics of History: Causal Link between Global Climate Fluctuations and Yersinia Pestis Contagion? University of New Orleans https://scholarworks.uno.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1632&context=td

Evans, J. A. S. 1996. The age of Justinian: the circumstances of imperial power. Routledge, New York.

North J., “The Death Toll of Justinian’s Plague and Its Effect on the Byzantine Empire,” Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History 3, no. 1 (Jan. 2013).

Linden Eug., The Winds of Change: Climate, Weather and the Destruction of Civilizations. NY, Simon & Schuster, 2006.

Little L. (edit) Plague and the end of Antiquity.

Procopius, History of the Wars, 7 Vols. trans. H. B. Dewing, Loeb Library of the Greek and Roman Classics, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1914), Vol. I, pp. 451-473

Procopius. 1935. The Anecdota. Harvard Univerisy Press, Cambridge, MA.

Sarris P., ‘The Justinianic Plague: Origins and Effects’, Continuity and Change, 17 (2002), p.169–82

Smith Chr., Plague in the Ancient World.

Temin, P. 2001. A market economy in the early Roman Empire. The Journal of Roman Studies 91:161-181.